By Niall Ferguson

Co-director of the Harvard Kennedy School’s Applied History Project

And

Eyck Freymann

Research analyst at Greenmantle

Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1934 (ASSOCIATED PRESS)

“There is a mysterious cycle in human events,” said Franklin Delano Roosevelt, accepting the Democratic nomination for president in Philadelphia in 1936. “To some generations much is given. Of others much is expected. This generation of Americans has a rendezvous with destiny.”

In the 20th century, many sociologists and historians flirted with the idea that generational changes could explain U.S. politics. The historians Arthur Schlesinger Sr. and Jr. wrote about “cycles of American history,” arguing that, as the generations turn, American politics rotates inexorably between liberal and conservative consensus. More recently, a new generational scheme has come into vogue. William Strauss and Neil Howe’s theory of the “fourth turning” predicts a crisis and a major political realignment every 80 to 90 years. (Strauss and Howe were briefly in the spotlight in 2016 after Steve Bannon praised their work.)

We are skeptical about cyclical theories of history. We are also aware of the slipperiness of generations as categories for political analysis. As Karl Mannheim pointed out more than 90 years ago, a generation is defined not solely by its birth years but also by the principal historical experience its members shared in their youth, whatever that might be. Nevertheless, we do believe that a generational division is growing in American politics that could prove more important than the cleavages of race and class, which are the more traditional focuses of political analysis.

Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is often described as a radical, but the data show that her views are close to the median for her generation. The Millennials and Generation Z—that is, Americans aged 18 to 38—are generations to whom little has been given, and of whom much is expected. Young Americans are burdened by student loans and credit-card debt. They face stagnant real wages and few opportunities to build a nest egg. Millennials’ early working lives were blighted by the financial crisis and the sluggish growth that followed. In later life, absent major changes in fiscal policy, they seem unlikely to enjoy the same kind of entitlements enjoyed by current retirees.

Under different circumstances, the under-39s might conceivably have been attracted to the entitlement-cutting ideas of the Republican Tea Party (especially if those ideas had been sincere). Instead, we have witnessed a shift to the political left by young voters on nearly every policy issue, economic and cultural alike.

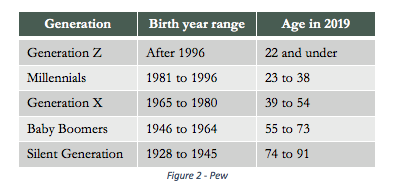

As a liberal graduate student and a conservative professor, we rarely see eye to eye on politics. Yet we agree that the generation war is the best frame for understanding the ways that the Democratic and Republican parties are diverging. The Democrats are rapidly becoming the party of the young, specifically the Millennials (born between 1981 and 1996) and Gen Z (born after 1996). The Republicans are leaning ever more heavily on retirees, particularly the Silent Generation (born before 1945). In the middle are the Gen Xers (born between 1965 and 1980), who are slowly inching leftward, and the Baby Boomers (born between 1946 and 1964), who are slowly inching to the right.

This generation-based party realignment has profound implications for the future of American politics. The generational transition will not dramatically change the median voter in the 2020 election—or even in 2024, if turnout among young voters stays close to the historical average. Yet both parties are already feeling its effects, as the dominant age cohort in each party recognizes its newfound power to choose candidates and set the policy agenda. Drawing on opinion polls and financial data, and extrapolating historical trends, we think that young voters’ rendezvous with destiny will come in the mid to late 2020s.

Today, the older generations have a lock on political power in Washington. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell are members of the Silent Generation. So are Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders, who lead in nearly every poll of the 2020 Democratic primary. President Donald Trump and the median senator and representative are Boomers. Of the nine justices on the Supreme Court, two are from the Silent Generation and six are Boomers. Yet the median American is 38—a Millennial.

Over the past year, the Democratic Party’s geriatric leadership has begun to feel the ground moving beneath its feet. For decades, moderate Democrats have kept a tight grip on the party’s platform. The 2018 midterm elections were a watershed. Boomers and members of the Silent Generation still make up more than three-fifths of the party’s House members and hold all major leadership roles. But newly elected members—including 14 Millennials and 32 Gen Xers—are driving the conversation on policy, from Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal to a recent resolution to withdraw support from Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen.

The Democrats have responded by moving left. In 2013, President Barack Obama signed a bill to cut the budget deficit by slashing hundreds of billions of dollars in spending. But already in 2019, a majority of the House Democratic caucus has co-sponsored a Medicare for all bill. Even those 2020 presidential candidates characterized as moderates, such as Kamala Harris and Cory Booker, have endorsed Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal, which calls for trillions of dollars of deficit-funded federal spending to transform America’s economy and its energy sector.

If Roosevelt was right, and demographics are destiny, then the Democrats are going to inherit a windfall. Ten years from now, if current population trends hold, Gen Z and Millennials together will make up a majority of the American voting-age population. Twenty years from now, by 2039, they will represent 62 percent of all eligible voters.

If the Democrats can organize these two generations into a political bloc, the consequences could be profound. Key liberal policy priorities—universal Medicare, student-loan forgiveness, immigration reform, and even some version of the Green New Deal—would stand a decent chance of becoming law. In the interim, states that are currently deep red could turn blue. A self-identifying democratic socialist could win the presidency.

By contrast, from the perspective of pure demographics, the GOP seems to be playing a losing hand. Unless Republicans can find a way to stop young voters’ slide to the left in the 2020s, the party will survive only if it can pull older voters—Boomers and the remaining members of the Silent Generation—to the right fast enough to compensate for the leftward shift of the young.

Read: The Millennial era of climate politics has arrived

Millennials cannot be blamed for concluding that the economy is rigged against them. True, in absolute terms, Americans under 40 carry less debt than middle-aged Americans. But their debt profile is toxic. Nearly half of it comes from student loans and credit cards. In contrast, 72 percent of the debt held by Americans aged 40 to 49 is mortgage debt, which comes with tax advantages and allows debtors to build home equity as they repay their loans.

Meanwhile, the job market has turned a college education into a lose-lose choice for many young Americans. In 2016, a single year of tuition, room, and board at a private college cost 78 percent of median household income. Most American families can barely afford to send even a single child to college without loans, let alone two or three. Yet young workers without a college degree are deeply disadvantaged in the workforce, and more so all the time.

Young people then struggle to stay above water financially after they graduate. The net worth of the median Millennial household has fallen nearly 40 percent since 2007. This is not because they eat too much avocado toast; it is because student loan payments consume the income that they would otherwise save. Headline unemployment figures show that the labor market is humming. It does not feel that way for Millennials, who have never experienced a “good economy.”

It is therefore unsurprising that large majorities of young voters support economic policies that Ocasio-Cortez describes as “socialist.” According to a Harvard poll, 66 percent of Gen Z supports single-payer health care. Sixty-three percent supports making public colleges and universities tuition-free. The same share supports Ocasio-Cortez’s proposal to create a federal jobs guarantee. Many Gen Z voters are not yet in the workforce, but 47 percent support a “militant and powerful labor movement.” Millennial support for these policies is lower, but only slightly.

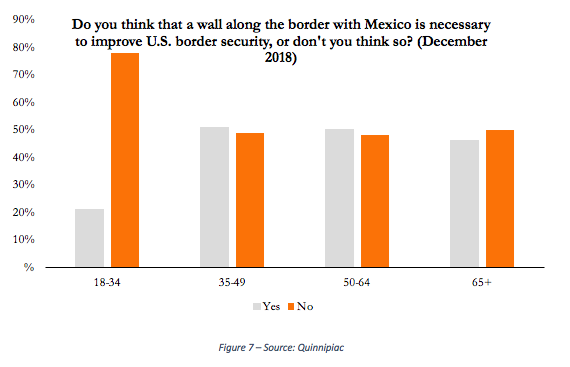

Younger voters are also far left of center on most other economic and social policies. They are particularly opposed to the Trump administration’s handling of immigration. Americans 35 and older are nearly evenly divided on the issue of President Trump’s border wall. Among voters under 35, this is not even a question. Nearly 80 percent oppose the wall.

Gen Z are not a trusting bunch. Students tend to believe that their college or university administration will do the right thing “always” or “most of the time.” Contrary to conventional wisdom, young Americans trust the military and law enforcement more than other institutions. But they take an extremely dim view of Trump, Congress, Wall Street, the press, and the social-media platforms where they get their news: Twitter and Facebook.

When the question is posed as an abstraction, most Gen Zers don’t trust the federal government either. But they favor big-government economic policies regardless because they believe that government is the only protection workers have against concentrated corporate power.

Philosophically, many Gen Zers and Millennials believe that government’s proper role should be as a force for social good. Among voting-age members of Gen Z, seven in 10 believe that the government “should do more to solve problems” and that it “has a responsibility to guarantee health care to all.”

Young voters are also far more willing than their elders to point to other countries as proof that the U.S. government isn’t measuring up. Gen Z voters are twice as likely to say that “there are other countries better than the U.S.” than that “America is the best country in the world.” As Ocasio-Cortez puts it: “My policies most closely resemble what we see in the U.K., in Norway, in Finland, in Sweden.”

Will Gen Z voters moderate their views after they enter the labor force? Probably not. Irving Kristol once joked that conservatives are liberals who have been “mugged by reality.” But the data don’t support this hypothesis. Most Millennials have already been mugged by reality: competing in the job market, paying taxes, and—for those 26 and older—taking responsibility for their own health care. In the process, they have lurched left, not right. On questions of political philosophy, Millennials are far closer to their juniors in Gen Z than to their elders in Gen X.

Even young Republicans have been caught up in this philosophical leftward drift. Gen Z Republicans are four times as likely as Silent Generation Republicans to believe that government should do more to solve problems. And only 60 percent of Gen Z Republicans approve of Trump’s job performance, while his approval among all Republicans hovers around 90 percent.

In short, Ocasio-Cortez is neither an aberration nor a radical. She is close to the political center of America’s younger generations.

Shadi Hamid: Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez understands politics better than her critics

Can the Democratic Party convert this tectonic shift into victory at the ballot box? Maybe, but not necessarily. As the party tries to harness its younger, more progressive wing, it faces three interrelated challenges.

The first challenge is the perennial problem of low youth turnout. Democrats have been working for decades to get more young Americans to vote. They have partnered with organizations such as Rock the Vote to make voting cool. They have invested heavily in social-media microtargeting and experimented with mobile apps that use peer pressure to drive up turnout. Yet they have never gotten youth-turnout rates high enough to swing a close presidential election in their favor. Since 1980, the percentage of eligible voters in their 20s who actually vote in presidential elections has held steady between 40 and 50 percent. For Americans aged 45 and up, voting rates have been far higher: between 65 and 75 percent.

History offers Democrats some reason for hope. The closer an American is to middle age, the more likely he or she is to vote. On the other hand, turnout rates are declining across the board, and it is the 30-to-44-year-old age bracket that has seen the steepest decline over the past four decades. Unless Democrats can show younger voters that their votes translate into policy change, they could find themselves trying to mobilize a generation that is permanently apathetic and politically disengaged.

Read: The voters Democrats aren’t really fighting over

The second challenge for Democrats is that most of the party’s traditional power brokers are older, and many of them consider the youngsters to be radicals, or at the very least political liabilities. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has declined to move forward with the Green New Deal. When freshman Representative Ilhan Omar made comments about Israel policy that were widely criticized as anti-Semitic, the Democratic-controlled House voted to voice its opposition. When the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee tried to block staffers from joining primary campaigns, Ocasio-Cortez told her followers to stop donating. These squabbles could easily lead to a rupture within the party.

The third challenge is that when young people organize, they do it in their own way and on their own terms. By The Washington Post’s count, between 1.4 and 2.3 million people attended the March for Our Lives in 2018, organized by school-shooting survivors from Parkland, Florida. Democratic candidates embraced the students’ cause and made gun control a central issue of the campaign. That may be one reason why early-voting turnout among 18-to-29-year-olds soared. But it was young people driving the agenda and the party following—not the other way around.

The best way for the Democrats to bridge these divides is to redouble the party’s focus on the issue that unites the coalition across generations: health care. In 2018, 41 percent of voters listed health care as their top issue. Three-quarters of them voted for the Democratic candidate.

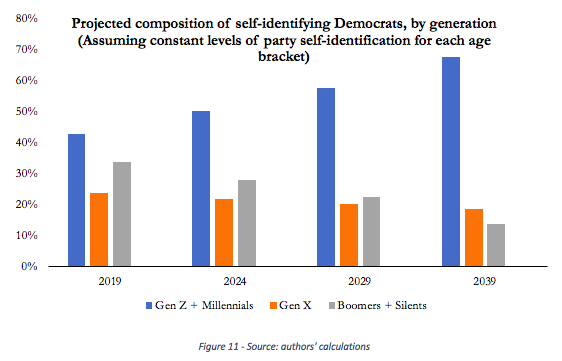

However, on most other issues, the demographic trend lines are clear: By the mid 2020s, if a preponderance of young voters support an issue, the Democratic Party will probably have no choice but to make it central to the platform. Today, 43 percent of self-identified Democrats are either Gen Zers or Millennials. By 2024, by our calculations, this figure might rise to 50 percent. If the Democrats are not already the party of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, they will be soon.

Does all this mean that the Republican Party is doomed? Perhaps not. Even as younger voters have moved to the left, Republicans have been sustaining themselves by winning an ever-greater share of older voters. The Silent Generation moved hard to the right under Obama. In 2008, 38 percent of its members identified as Republicans. By 2016, that figure had risen to 48 percent. But the youngest members are now 75, and they will not be around forever. So Republicans are racing against the clock to pull nonaligned Boomers into the coalition. (It doesn’t hurt that Boomers now comprise fully two-thirds of the House Republican caucus.)

But how? Tax cuts are part of this strategy, but as voter reactions to the 2017 GOP tax bill showed, it’s a policy that yields diminishing political returns. A more important gambit was revealed in Trump’s State of the Union address in February, which drew a link between the disastrous regime of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela and the emerging Democratic agenda. “We are born free, and we will stay free,” the president declared. “Tonight, we renew our resolve that America will never be a socialist country.”

As a small but growing number of prominent Democrats embrace the label “socialist”—or “democratic socialist,” as Sanders terms it—Republicans smell blood in the water. More than half of young voters may have a positive view of socialism, but sizable strong majorities of all age groups over 30 prefer capitalism. Indeed, voters over 65 feel more positively about capitalism today than in 2010, when Gallup began to ask the question. It remains to be seen whether the 2020 Democratic primary can normalize the word socialist. For now, however, it is clearly a liability for the Democrats in a national election.

Then comes the question of immigration. As we have seen, younger American voters strongly disagree with the Trump administration’s aggressive efforts to “build a wall” along the country’s southern border or limit legal immigration from Muslim-majority countries. This reflects the profound difference between the generations in terms of racial composition. Fully 85 percent of the Silent Generation is white; only 12 percent is black or Latino. Among the members of Gen Z, by contrast, only 54 percent are white, and 38 percent are black or Latino. A far larger proportion of Gen Z also identifies as mixed-race. This divide will widen further in the coming years because of immigration, birth-rate differentials, and the fact that white Americans at age 75 have a higher life expectancy than African Americans.

Negative views of immigration are based on more than just the economic argument that newcomers are lowering the wages of native-born workers or exacerbating shortages of housing or public goods. Such views have a significant cultural component, too. Needless to say, Donald Trump specializes in whipping up the anxieties of older voters about what they see as alarmingly rapid social change.

But the Republicans need to find ways of winning over aging Boomers, many of whom are squeamish about being branded as racists. That is why it makes political sense for them to broaden the culture war, making it about much more than immigration.

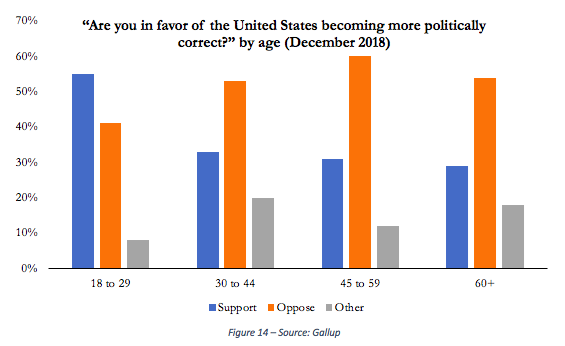

According to a Marist poll last December, a sizable majority of Americans under 29 want to see the country become “more politically correct.” But voters over 30 oppose the rise of political correctness by a factor of nearly 2 to 1. This is a wedge issue that Republicans will exploit with gusto.

Republicans will be happy to note that middle-aged voters are even more strongly opposed to political correctness—and all that they believe this entails—than retirees. This trend is unlikely to reverse as the Democratic Party, under the influence of the Ocasio-Cortez cohort, brings issues of cultural and social justice closer to the core of its platform. Nor will it resolve itself as these middle-aged voters’ children become teenagers and go to college, where the culture of social justice is most explicitly disseminated.

Liberals may retort that social values can change with surprising speed. Couldn’t PC culture follow the same trajectory as interracial relationships, gay marriage, and legal marijuana—once taboo, now mainstream?

Perhaps it can, but we think it probably won’t. The gay-marriage debate was about the legal status of a minority. The PC debate is about norms of expression that affect everyone. For many older voters—and not just conservatives—campus politics has become a wholly alien parallel world of safe spaces, trigger warnings, and gender-neutral pronouns. That helps explain the president’s recent executive order to cut off federal funding to colleges that fail to uphold free speech. By taking campus politics national, the GOP will try to pry centrist Boomers and older Democrats away from a party more and more driven by the values of progressive academia.

Generational conflict likely won’t swing national elections until the 2020s, depending on turnout rates and attitudinal shifts among the Boomers. In the short run, this is probably good news for the GOP, as Democrats lurch to the left on identity-based issues that turn off older voters.

Yet Trump’s strategy of single-mindedly courting members of the Silent Generation with issues such as immigration, the evils of socialism, and campus free speech is not a long-term solution for the Republican Party. The more the GOP belittles the preferences of younger voters, the more it risks forging them into a left-wing bloc.

In the 2020s, the Silent Generation will fade from the scene. This will happen at precisely the same time that history suggests younger, more left-wing voters will start to vote at higher rates. To attract more Boomers, and some Gen X men, the GOP may paint the Democrats as radical socialists and do all it can to fan the flames of the culture war. To avoid splintering along generational lines, Democrats will likely redouble their focus on health care, a rare issue that unites the party across all age groups.

In short, America’s political future will be determined by the outcome of the generation war. Can the Millennials and Gen Z organize themselves into a cross-party political bloc? If they succeed, they can dominate U.S. politics within the next 10 years, and the Democratic Party will follow them. But if Republicans can persuade enough Boomer Democrats to switch sides by effectively turning politics into a nationwide culture war, Trumpism could prove longer lived than most commentators today assume.

Will there be any areas of common ground in a political future fueled by intergenerational warfare? Not many. But one suggests itself. Even as the rising cost of Social Security and Medicare place growing pressure on the budget, neither side will have much political incentive to fight for deficit reduction. Republicans’ dreams of privatizing Social Security and trimming Medicare died forever with Paul Ryan’s retirement last year. If anything, the two parties might collaborate to expand and shore up welfare programs, ramping up the deficit in the process. The experience of Japan suggests that, so long as interest rates remain low enough and the demand for government bonds high enough, difficult fiscal decisions can be postponed for much longer and public debt accumulated to much higher levels than conventional economics led us to expect.

When FDR spoke of a new generation’s “rendezvous with destiny,” few in his audience imagined that it would take the form of another world war. Democrats who aspire to the presidency are often tempted to talk in similar, uplifting terms. Barack Obama liked to quote Martin Luther King Jr.’s remark that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” though for Obama it became an arc of history, invariably bending his way. Few Democrats, even on the night of November 8, 2016, could conceive that the arc of history might bend toward Donald Trump.

Cyclical theories that seek to explain and predict political change in terms of generational “turns” should be therefore be treated with skepticism. If, as Mannheim argued, generations are shaped by the big events of their youth, then—who knows? —a single black swan could turn today’s kids into Ocasio-Cortez’s worst nightmare: Generation T for Trump. After all, it has been asserted, to the glee of his critics, that the president’s vocabulary is that of a fourth grader. Sure, but that also means fourth graders can understand what Donald Trump says. Today’s fourth graders will be voting in 2028. Perhaps they, too, will be as “woke” as Generation Z currently is. But history teaches us not to assume that.

In 1960, Friedrich Hayek predicted in The Constitution of Liberty “that most of those who will retire at the end of the century will be dependent on the charity of the younger generation. And ultimately not morals but the fact that the young supply the police and the army will decide the issue: concentration camps for the aged unable to maintain themselves are likely to be the fate of an old generation whose income is entirely dependent on coercing the young.” It hasn’t turned out that way at all—a salutary warning that it is much easier to identify generational conflicts of interest than to anticipate correctly the political form they will take.

______________________________

NIALL FERGUSON is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution and a co-director of the Harvard Kennedy School’s Applied History Project. He is the author of Kissinger, 1923–1968: The Idealist and The Square and the Tower: Networks and Power from the Freemasons to Facebook.

EYCK FREYMANN is a research analyst at Greenmantle and a Henry Scholar at St. Edmund's College, Cambridge. He is the author of the forthcoming book The Emperor's New Brand: One Belt One Road and the Globalization of Chinese Power.